As the Chao Center’s mission statement indicates (https://chaocenter.rice.edu/about/mission-and-history), from its very beginnings, the Center’s research, teaching, and outreach activities have focused primarily on the transnational, transhistoric, diasporic, and global movements of the peoples and cultures of Asia––an expansive “Asia without borders” approach to Asian Studies. The Center has also encouraged international scholarly cooperation, especially between individuals and institutions in Asian countries and other Asian cultural environments (for example, overseas communities). Thus, when two of our faculty, Nanxiu Qian (Chinese Literature) and Richard J. Smith (History), proposed an international conference focused on the way that texts written in Asian languages circulated in premodern East Asia (China, Japan, Korea, the Liuqiu/Ryukyu Islands and Vietnam, also known as the “Sinosphere”), we readily gave our support––not only in terms of funding but also in terms of administrative assistance.

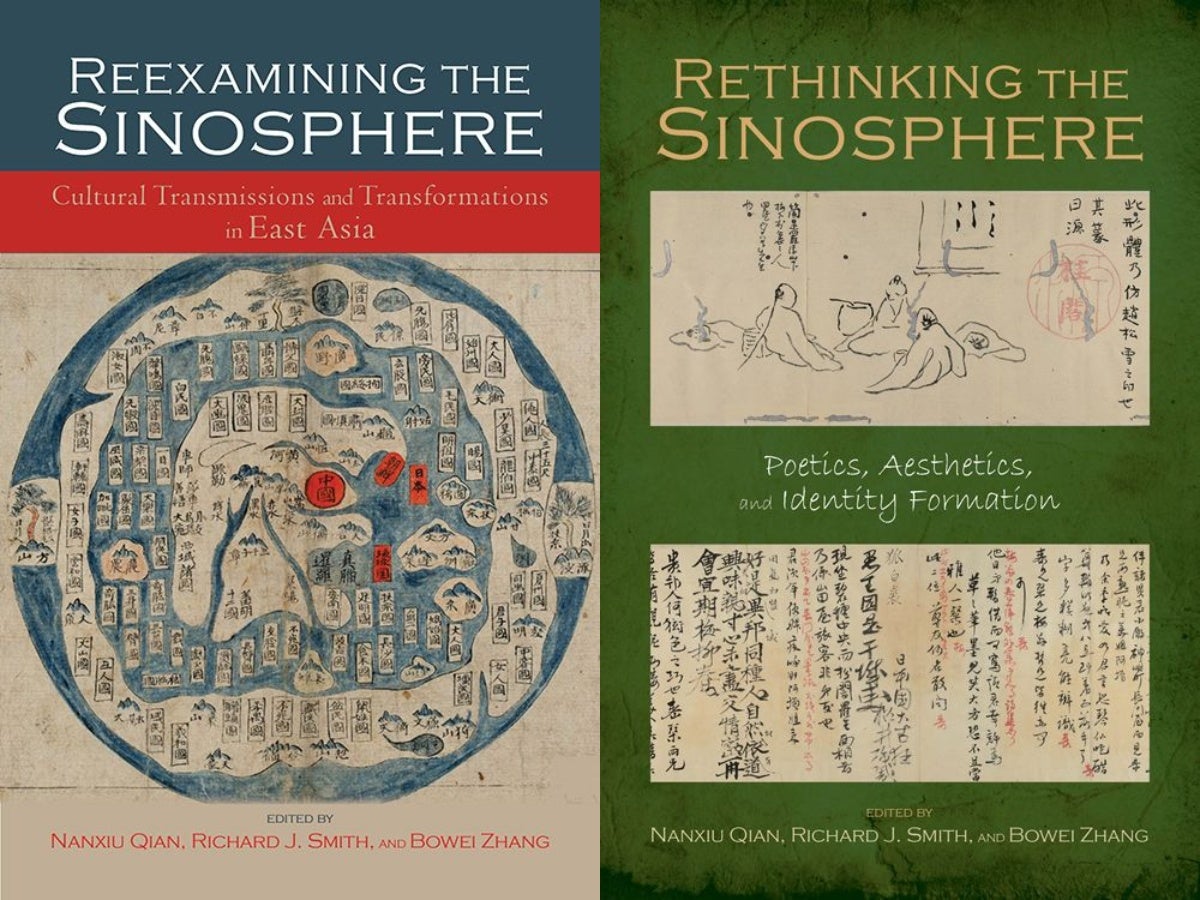

Our support was complemented by funding from the Office of the Provost, the Dean of Humanities, the Humanities Research Center, and other Rice organizations. Professors Qian and Smith also received a generous grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities, which provided funds for a preliminary conference in China (2016) and a full-scale international conference at Rice (2017) titled “Reconsidering the Sinosphere: A Critical Analysis of the Literary Sinitic in East Asian Cultures.” The project also involved publication of the conference papers in two volumes. These volumes––titled Rethinking the Sinosphere: Poetics, Aesthetics, and Identity Formation and Reexamining the Sinosphere: Cultural Transmissions and Transformations in East Asia––have just appeared in print from the Cambria Press (March 2020), and so we asked the Rice co-editors, Professors Qian and Smith, to talk about the genesis of the two books. A third co-editor, Professor Bowei Zhang of Nanjing University in China, kindly allowed the two Rice professors to speak for him.

Chao Center: Who came up with the idea of an international conference on the Sinosphere, and why was that particular term chosen?

Smith: Nanxiu came up with the idea, based on her long-standing professional relationship with Professor Bowei Zhang, one of the first scholars in the world to institutionalize the transnational study of classical Chinese, also known as literary Sinitic. The term Sinosphere refers to the area in which literary Sinitic was the principle medium of written communication for premodern elites who spoke radically different and mutually unintelligible languages. Literary Sinitic was, one might say, the “Latin” of East Asia.

Qian: The problem with most past studies of documents written in literary Sinitic was that they generally adopted a China-centered approach, treating the other countries of East Asia as lesser versions of China, downplaying the unique histories of these countries, and ignoring the diverse cultural consequences of their individual use of literary Sinitic. This Sinocentric approach was completely unacceptable to us, and so we invited scholars to our conference who had an especially broad perspective on East Asian history, literature and culture.

Smith: That’s correct. Although literary Sinitic was “invented” in China more than three thousand years ago, it had a life of its own in each East Asian country into the twentieth century––modified significantly by a complex and continuous process of cultural interaction, exchange, and transformation. For us, then, the term Sinosphere refers simply to the broad geographical area in which the literary Sinitic found expression in elite written discourse; it does not privilege China in any way.

Chao Center: How did your collaboration on this project begin?

Qian: Rich and I have had similar intellectual interests for decades, despite our different disciplines. We both work with literary Sinitic texts, and we have both been fascinated by the way that certain of these texts have traveled, and especially how they came to be transformed in the process. My work has focused primarily on a book titled Shishuo xinyu (A New Account of Tales of this World), and Rich’s has focused primarily on another book called the Yijing or Classic of Changes. But we have since gone on to study other textual transmissions, inspired by our colleagues from East Asia and Europe, as well as Canada and the United States.

Smith: In planning our conference we gave special attention to the need for a broad representation of scholars from China, Taiwan, Japan, Korea and Vietnam. Thanks to our various academic connections in these areas, and with generous financial support from the National Endowment for the Humanitites, we were able to attract a truly remarkable group of comparative historians and specialists in comparative literature to our 2017 conference. As Nanxiu has indicated, these scholars continue to inspire us.

Chao Center: Tell us about the two conference volumes.

Smith: Well, the first thing to say is that Nanxiu organized and chaired the 2017 conference at Rice with very little help from me. Indeed, I was unavoidably out of town for the entire meeting. I did, however, prepare a paper that was circulated to the participants before the conference, as well as a powerpoint presentation that Nanxiu kindly delivered. When it came to editing the two conference volumes, I was able to be more helpful, in part because Nanxiu arranged to tape the entire proceedings, giving me a chance to “participate” after the fact, and to have a good sense of how our contributors felt about their material.

Qian: Rich is being too modest. He assisted in the organization of the conference for several months prior to the meeting, and maintained close phone and email contact with me and the participants both before the meeting and during it.

Chao Center: How would you describe the content of each conference volume?

Smith: I should mention that this is actually the second time that Nanxiu and I have coedited a conference volume. The first, also based on an NEH-endowed Rice conference, which I did attend and helped to chair, was titled Different Worlds of Discourse: Transformations of Gender and Genre in Late Qing and Early Republican China (2008). The fact is, Nanxiu and I have always worked extremely well together as a team.

Qian: In a certain sense, our separation of the material in the two Sinosphere volumes has been arbitrary. The subtitle of Reexamining the Sinosphere––“Cultural Transmissions and Transformations in East Asia”––applies to all of the chapters in both volumes, and the subtitle of Rethinking the Sinosphere––“Poetics, Aesthetics, and Identity Formation”––applies to many of the chapters in the Reexamining volume. The differences in content between the two books are largely matters of emphasis.

Smith: Above all, what we sought to do, in addition to discussing the travels of literary Sinitic texts, and their eventual “domestication” in different cultural environments, was to give attention to issues of class, gender, ethnicity and identity across time and space. We also wanted to explore artistic genres as well as literary ones.

Qian: Another question that our Sinophere volumes addressed was the effect that literary Sinitic texts had on scripts that bore little or no relationship to them––whether these writings were produced by ethnic minorities within China Proper or by Inner Asian peoples on the periphery, including Mongols, Manchus, Tibetans and Inner Asians of all sorts.

Smith: The essays in the two volumes also draw attention to ongoing scholarly debates surrounding issues of definitions, terminologies, periodization and the question of how far our spatial and temporal analysis should extend.

Chao Center: Can you give us an example?

Qian: Sure. For many decades Jesuit missionaries in China and Vietnam, and for shorter periods in Japan and Korea, learned literary Sinitic and then rendered it into their own written scripts (mainly Latin, French, and Italian) for consumption by Europeans. How did this process compare with similar translation and transmission processes in East, Central, and Western Asia?

Chao Center: So what conclusions were you able to draw in your two volumes?

Smith: One conclusion is that many issues connected with the travels and transformations of literary Sinitic texts in East Asia and beyond remain to be explored and discussed more fully.

Qian: Perhaps the major conclusion that emerges from the articles in the two books is that although there was undeniably a shared culture in premodern East Asia—one that justifies treating the area as a coherent whole—this shared culture can only be seen clearly in transnational and cross-cultural perspective.

Smith: Most definitely. I would add that although many elements of this shared culture originated in the area we now refer to as China, these elements were seen by intellectuals in premodern East Asia as universal markers of civilization, not necessarily particular to China.

Rethinking the Sinosphere: Poetics, Aesthetics, and Identity Formation can be purchased through Cambria Press, here. A description of the cover art can be found here.

Reexamining the Sinosphere: Cultural Transmissions and Transformations in East Asia can be purchased through Cambria Press, here. A description of the cover art can be found here.